A part of this viewing list: Criterion Collection Spine #240: Yasujiro Ozu’s Early Summer.

As contemporary dramas go, Ozu’s Early Summer manages to select issues that are both timeless and practical in the instant of their genesis. It is at once a story of post-war Japan and family crisis, and a chance to examine both reconciliation and resignation to the altering status quo. [Can you tell I’m trying to sound as pompous as possible?]

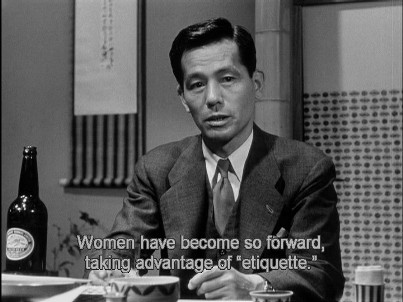

Ozu’s vision of postwar Japan is a good fulcrum for comparing Japanese cinema that focuses on the traditional lifestyle, and that which takes rapidly assimilated Western culture as its focus. In this film, women in traditional garb visit modern offices and sit in chairs and white-coated doctors of internal medicine come home to paper walls and extended family. Lanes are still made of dirt, but women ride the train into Tokyo to earn their paychecks. It is the changing role of women, and their immediate and confident embrace of opportunity [at least in the film’s world] that ends up causing the relatively minor problem that loosely serves as the plot.

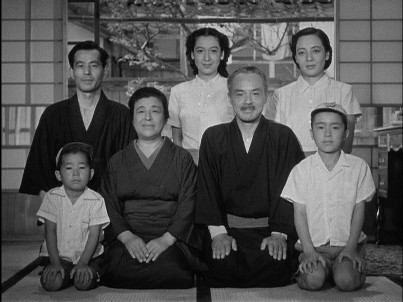

Three generations of the Mamiya family live in the same house, a not uncommon set-up in traditional Japan. Noriko, however, is the untraditional family member. At twenty-eight, she remains happily unmarried. Everyone, including her boss, wants to get her hitched. They focus on men who have good prospects, not worrying about love in the slightest. The match-making is meant to improve the family’s lot, any happiness would be a mere byproduct. Noriko, mainly through her silence, is polite but unwilling to commit to marrying a man her boss has recommended to her. Despite all of this, her family acts as if she is already as good as married, and there is a palpable sense of relief. Then, Noriko chooses to marry a widower with a child, a man who also has good prospects and is her childhood friend. She doesn’t admit that she is in love, but she says she knows Yabe well enough that she can trust him all her life.

The family doesn’t like the fact that she made this choice without consulting them, nor do they like that Noriko will have to move to Akita. Noriko’s parents had promised Uncle that they would move to Yamato when Noriko married. Through her own decision for marriage, something all wanted for her, she scatters the family. Yet despite all of this anger and poignancy, the love of the family sustains. The grandfather is resigned to the changes but thankful for the happiness he’s had, Koichi is focused on his doctorly ambitions, and Noriko fully embraces the new world that is opening for her. They all know the changes are inevitable.

I have to say that I really like Ozu’s style. Apparently he only used two height setups for his camera on a tripod, and camera movement is almost nonexistent, and serves more as a end-of-scene flourish and segue than as anything else. Since he only uses two heights, the framing of his shots is determined only by the distance he puts the camera from the action. Cuts in retain the same height but alter the frame significantly, nonetheless. He also likes to hold shots after the scene is ended to allow a brief moment of palate cleansing before the next action begins. I’m quite interested in watching more by Ozu.

• Criterion Essay by David Bordwell

• Jim Jarmusch on Ozu [from Art Forum magazine]

• An Ozu fan page