A part of this viewing list: Criterion Collection Spine #294: Anthony Asquith’s The Browning Version.

Summer is over and since all the children are heading back to school I thought I’d better pick up where I left off 4 months ago and start watching Criterion Collection films again. This film happens to take place at the end of a school year, but no matter. The Browning Version is a movie based on Terence Rattigan’s play of the same name. Rattigan also wrote the screenplay for this film, which won an award at Cannes over 50 years ago. The action flows around an old classics teacher named Andrew Crocker-Harris who has been broken down by his wife and his nearly 20 years of teaching.

Crocker-Harris is everything that people loathe in a person, always punctual, unbendingly respectful of every rule, no matter how trivial, and apparently without a sense of humor or any other emotion. He is consistently referred to as a dead man, a corpse, and a man without a soul. His students live in fear of him, his wife has cuckolded him, and he is being replaced by a younger more modern teacher. Even the establishment is casting him aside without a pension and compounding the injury by asking him to give his give up his place of honor at the valedictory convocation.

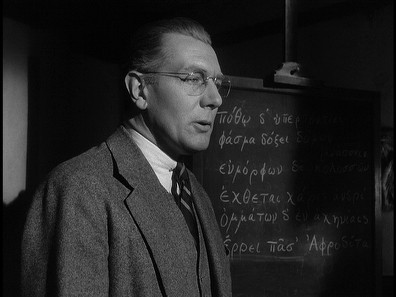

There is one young student who feels sorry for the chap and makes efforts to break through the accretion of apathy that has immobilized the once brilliant Crocker-Harris. His interest in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon reminds Crocker-Harris of his past youthful exuberance regarding the same play. He opens up slightly and tells young Taplow that he once attempted his own translation in rhyming couplets, but never completed it. Later, Taplow buys Crocker-Harris the Browning version of the Agamemnon, and inscribes, in Greek, the dedication “God from afar looks graciously on a gentle master.” [For an interesting reflection and reverse engineering of the Greek usage in the film see here.] This dedication, coming as it does at the end of a day full of blows, touches Crocker-Harris so deeply that he begins to cry. Though his wife still tries to crush his soul, this small act eventually gives Crocker-Harris the strength necessary to accept responsibility for his past and the determination to do better in the time left him.

Two thematic elements were highly visible to me in this film. The first is the obsession with time as a diegetic motive. Crocker-Harris, of course, is the most obsessed with it, and the constant bell-ringing and declarations of what time it is [for dinner, for fireworks, for tea] make it seem as though despite all his efforts, time is merely passing him by. The second theme is the film’s definite relation and interaction with The Agamemnon. In many ways Crocker-Harris’s life mirrors the life of Agamemnon, even down to the supporting characters, but the difference is that Agamemnon is physically killed, while Crocker-Harris is only soul-dead. This creates an interesting space for diversion from the original and allows the film more room for contemporary concerns.

Asquith’s shot selection is excellent as well. Crocker-Harris is usually seen in profile or slightly from behind, adding a sense of alienation and unapproachability to his already taciturn nature. Even when he breaks down and cries, we only see his back. Only toward the end, when Crocker-Harris begins to take charge of his life again, does he start to take an active position in the shot. Michael Redgrave’s acting is superb and fits hand-in-glove with Rattigan’s screenplay. While the film isn’t flashy at any point, for fans of drama and elegance, this is a film to see.

• Criterion Essay by Geoffrey MacNab

• Transcription and clip of Crocker-Harris’s farewell speech.

• Wikipedia article on Terence Rattigan’s play.

• The Browning version of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon at perseus.tufts.edu. [I’m getting flashbacks]