A part of this viewing list: Criterion Collection Spine #382: Stuart Cooper’s Overlord.

I was contacted by a NYC marketing firm to review Overlord, which was released on the 17th. So hey, free DVD. This is the second time that someone has happened along my movie reviews and asked me to do one for them. I must be doing something right. Incidentally, this film will be shown at the Cleveland Cinematheque in October. Catch it if you can.

Overlord has an interesting cinematic niche. It is composed, in significant amounts, of World War II stock footage [mostly from the Imperial War Museum]. This footage has been seamed together with plot-oriented shots that were deliberately cinematographed to look like stock footage. John Alcott [Kubrick’s regular choice for cinematographer] was in charge of this, so quality is expected and delivered. The story follows a young British man who is dutifully making his way toward the war, culminating in D‑Day. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a film that does such a good job putting its main character in context with the events in the world around him.

The film has an objectivity and a subjectivity that rub against each other like flint and tinder. The objective vector concerns the mind-bogglingly vast resources and activities associated with the war effort; from civilians fighting fires after air raids to dive bombers going after battleships and destroyers, to the mustering and transportation of troops troops troops. It is like an 80 minute version of a Frank Capra “Why We Fight” minus the forced jovial voice-over and editorial propaganda. The film is bookended with long, wordless sequences of this action; in the beginning it immerses the viewer, but by the end it has a completely different flavor.

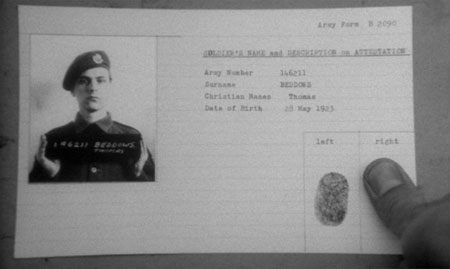

This whole element is so dense that without the subjective angle to balance, a viewer could easily become overwhelmed. Tom Beddows adds the human element. He begins the film as a man with regard for the act of defending his country that has likely been passed down by Tom Beddows, Sr. who fought in the First World War. By the end, this regard has been steadily degraded through disgruntlement and cynicism; Beddows becomes completely nihilistic [burning his letters to home]—all before he’s left Britain. This correlates with the intercut objective stock footage elements. The dehumanized war machine dehumanizes. It is a bit reminiscent of Douglas Adams’ Total Perspective Vortex, sans humor.

I should clarify what I mean when I use the word objective. The clips themselves are documents, with only the most vestigial resonances of propaganda. The way they are used by Cooper is not objective, they are meant to wind the internal springs of Beddows to their breaking point. Cooper’s motivation is a product of the Vietnam era; looking at World War II from this perspective is quite interesting. The training sequences, and Beddows transformation into near roboticism become a bit sinister; almost as if someone of complete indifference has planned each element in the dehumanization process. In the end even Tom Beddows dreams are tinged with an indifferent regard to the death he knows is coming. It’s not surprising that the war gets to him before he gets to it.

• Criterion Essay by Kent Jones.

• Criterion Press Release with links to many reviews and other press information in a .zip file.

• Clips: 1 and 2.