A part of this viewing list: Criterion Collection Spine #30: Fritz Lang’s M.

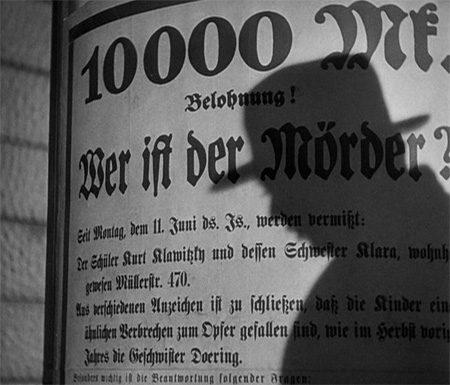

Fritz Lang always blows my mind. The precise craftmanship in all of his films, the exactly correct framing for a shot, the inspired, slight, understated camera movements, the chiaroscuro and beauty of the black and white would be worth watching in a film without anything resembling a plot. But Lang is not merely good at one or two aspects of filmmaking. He is good at making films, complete worlds unto themselves. M is a world of suspicion, where neighbors are encouraged in paranoia and tale-bearing, where the innocuous becomes sinister, and a budding fascist government controls the public through its efforts to find and stop a faceless enemy. It was made in 1931, anticipating the Third Reich by a few years. That’s just the macro level. On the micro level, the psychological portrait of a child-killer is immediately abhorrent and understandable, and the steps into Hans Beckert’s [played wonderfully by Peter Lorre] mind are so well-written, portrayed, apt and surprisingly potent that the film, which is largely run-of-the-mill police procedural for the most part, culminates in an unexpected explosion of emotion that a viewer is left with something approximating a thousand-yard stare.

If we have to pick one word for this film to be about, it is likely repression. The reason Beckert acts as he does, even though he knows he is mad and should not, is because he has no option in his society but to repress his reprehensible desires. Even a verbal expression of his desire to have sex with little girls and then murder them is so outside the norm that it would likely cost him his life or at least a few teeth. Stuck as he was, forced to internalize and cocoon himself from the everyday of everyone else, it is unsurprising that he would essentially disappear, so innocuous that no clues appear apart from his habit of whistling Peer Gynt as he seeks new prey. Similarly, his writing of a letter to the police, and then the papers attests to his desire, no matter how now malformed, to have communication with society at large. This is all possible to learn without actually seeing his face, or hearing him speak. Sound was a relatively new feature in film at this time, and its ambient use by Lang, its appropriate and heightening omissions, and its laconic dialogue make the final soliloquy by Beckert all the more effective.

The fact that even the criminals, societal edge-cases themselves, want to destroy Beckert with no qualms is telling to his extreme deviance. Yet, when he explains the motivations and guilt that drive and torment him, heads nod even among the kangaroo court. These are people who know what it is to sin, though for the most part they can control it. The coda is so terse that it was either meant to be that way or some of the missing footage belongs at the end of the film, but no matter the reason, it attests simultaneously to the paradoxical ethical and reasoning satisfaction of the rule of law and the passionate, emotional dissatisfaction of justice not being served. The tale of serial killer becomes analogous to the life of every person, only taken to an extreme; and the character sketch of a doubly fear-driven society adds another facet to Lang’s idea that vice and viciousness are all too easily encouraged with any person.

- Criterion Essay by Stanley Kauffmann

- Criterion Contraption Review

- Fritz Lang’s M

- ‘M’: Fritz Lang’s Dark Masterpiece, Still Shocking After All These Years

- M (Murderer Among Us) a film by Fritz Lang [Plenty of Stills]

- ImagesJournal Review

- Jonathan Rosenbaum Review

- Senses of Cinema on Fritz Lang

- Broken Projector Review

- Watch the whole movie on Google Video

- Watch and Download the whole movie from Archive.org