Category: Cinema

Reviews of movies Adam has seen or films he has worked on.

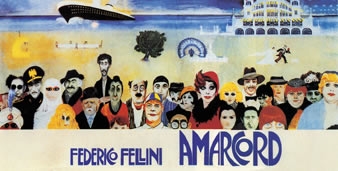

A part of this viewing list: Criterion Collection Spine #4: Federico Fellini’s Amarcord.

You can get excellent broad-spectrum treatments of this film by reading the review and essay I’ve linked to at the bottom of this page. I’m not going to give you a broad-spectrum treatment at all, because to me Amarcord is all about masculinity from beginning to end. The film is definitely a satire and full of political commentary, but all of it is seen through a testosterone lens that it becomes one of the most comprehensive lists of manly posturing that I’ve come across. This is not a bad thing. Film semioticists like Christian Metz probably love this film because it can come apart and be reassembled in so many different ways.

There is plenty of male lust, the film opens with a spring ritual, where they burn a witch in effigy and men prove their virility [or perhaps hope to keep it] by jumping over the hot ashes of the bonfire. The women know that they are the objects of the scopophilic gaze, but instead of reducing them to objects it puts them in a position of power, mainly because the men are so horny that they can’t help but be enthralled. Every man stops and stares, [and even most of the women as well] when the new whores are brought to the brothel in town. There’s also Volpina [that means fox] who pretty much acts like a fox and looks like a fox and is a nymphomaniac. Most interesting is Gradisca [a nickname, which means “Whatever you want” or something similar], who has a “reputation” that no one really believes in, and who is still the object of the most slack-jawed panting behavior on the part of the male populace of Rimini. There is also masturbation, masturbatory fantasies [during Confession no less [!], and at other times], and a rather disturbing scene where the adolescent Titta [a stand in for Fellini, cf. The 400 Blows for similarities] is almost suffocated by enormous German boobs. Lust is probably the most common theme because the film harks back to Fellini’s own adolescence, but there is more to a man than that.

What else do you ask? Power and violence of course! The “story” of the town takes place while Italy was under Fascist control. When the Fascists pay a visit we get hero-worship of Mussolini [including a male fantasy where Il Duce lets the fat kid marry his crush], marching about and intimidation on the part of the blackboots [not bootblacks] and eventually a little bit of political strongarming when the Fascists pour castor oil down Titta’s father’s throat because he isn’t a card-carrying Fascist. Since Italy was considered a Fatherland at this point, the fact that the entire city goes out to sea to watch the passing of Il Rex [a huge passenger liner, the Pride of the State!] adds another little corner to the masculine edifice of the film.

The most beautiful and rich syntagmatic blahblah is a scene during the first snowfall in winter, when a loose peacock flies about town crowing, lands in the square, and spreads its arrogant plumage to a large group of men who are watching. I don’t want to talk much about this part, because it is so perfectly done in the film that any other discussion of it makes it less than it is. I’ve already said to much about it.

There are glimpses of manhood behind the masculinity, but only glimpses, which is probably appropriate. Titta’s crazy uncle Teo ends up in a tree, anguished and violent, yelling that he wants a woman. When Titta’s mother is ill [possibly from being out on the sea waiting for Il Rex all night], we can see the helplessness that his father feels but tries to hide. When she dies, Fellini pulls off another masterful piece of filmmaking by allowing one sob from Titta and a shot of an empty bed before cutting immediately to the funeral. Some things are too grievous to be observed, and the lack of observation makes the emotion all the stronger. Of course, Titta’s mom isn’t even in the ground yet before he is checking out one of his distant relatives.

There is also the gentle fatherly figure of the Lawyer, who gives us a bit of narration throughout the film, the pathological tale-teller Biscelin [who once porked in one night 28 out of the 30 concubines that a visiting Emir brought with him] and some dude who we never see doing anything but riding around on his motorcycle and almost running people over. There is also a motor-car race [where the fat kid finally gets over his crush, in a totally different type of masturbatory fantasy]. I’m probably forgetting a few things, but I’m all out of machismo and don’t want to write anymore.

• Roger Ebert Review

• Criterion Essay by Peter Bondanella

• The Criterion Contraption’s review.