Category: Cinema

Reviews of movies Adam has seen or films he has worked on.

A part of this viewing list: Criterion Collection Spine #34: Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev.

For a film named after and about a single man, Rublev is remarkably absent. Instead Tarkovsky exposes and lingers on specific events that intertwine and illuminate the life of Russia’s most famous icon painter. A chance encounter with a jester, the observation and unwitting participation of a pagan ritual, the casting of a bell — all are significant moments in the intellectual, spiritual and moral development of Rublev; and right along with this, the hand of Tarkovsky adds simple, perfect, brushstroke moments to emphasize the lesson that Rublev is about to learn. The wide aspect ratio [2.35:1] does less to stretch the shot arrangements and acts more as a focus, mainly because the long takes and extended pans and tilts Tarkovsky was so fond of make it seem as if the film was matted in post production. The extremities of distance that appear in shot after shot, and the surprising introductions and revelations this technique allows, often give the film a disturbingly oneiric feel. There are times when the viewer might be watching Rublev’s imagination, but transitions to and from the actual and the flashback are so smooth as to be nonexistent, and a viewer is left filled with the same sense of doubt that consumes the protagonist.

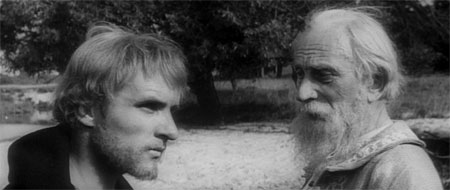

In a similar fashion to Rublev’s physical absence, we never see him do the painting he is so famous for. Mostly we are treated to discussions on aesthetics that would appear superficial to anyone who isn’t concerned with the effect their art will have on the immortal souls of all who view it, or the most spiritually accurate ways to portray a saint or Biblical anecdote. The film ends before Rublev makes his way to Trinity monastery, as an old man, to complete his most famous work. The fact that Tarkovsky deliberately ignores the most well-known fact of Rublev’s life in favor of apparently tangential notes actually makes the appreciation of the Rublev oeuvre more refined. Rublev becomes a man who is tortured by the very gift that makes him famous and allows his best effort to glorify God. He sins, terribly, in his own eyes, and gives up speech and painting for decades as penance. Only when he encounters himself in a gifted young man does he realize that his talent and its accompanying terrors belong together, and that by denying them he denies God. Really, only then, do we see him relax, or realize that throughout the film, no matter when we’ve seen Rublev, he has been taut as piano wire.

Politically and historically, the film was immediately banned in the USSR upon release. This kind of thing always interests me in an aggravating way. It is hard for me to understand how so much of Russia’s artistic production that was antagonistic to the Soviet cause got made in the first place, likely with state-funding. And how their makers often didn’t get into trouble. Andrei Rublev doesn’t seem like a particularly politically offensive film; although it seems to indicate what has held through the centuries, Russians peasants are dirt-poor and crushed beneath the petty squabbles of the nobility. To jump to the wrong continent for a trenchant phrase: “When two elephants are fighting, the grass is what suffers.” Which is certainly true in this film. Whether the violence and bickering of the Princes, to the Tatar invasions, the poor can’t win for losing. Tarkovsky works hard to make this violence and its everyday callous expectation come through, and it does effectively, mostly through the auspices of animal cruelty. In such a world as Rublev lived in, it is not surprising he was so conflicted in the exegesis of his work. This is a fabulous movie.