Category: The Criterion Collection

My neverending quest to watch all of the Criterion Collection films.

A part of this viewing list: Criterion Collection Spine #112: Jacques Tati’s Playtime.

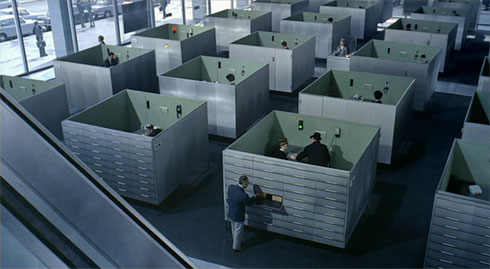

M. Hulot is back, at least part-time, for his last appearance in cinema. Playtime continues Tati’s tradition of satirizing the mundane, but unlike M. Hulot’s Holiday, this time the focus is on modernity rather than leisure time. Filmed nearly 15 years after Holiday, Tati has polished Hulot’s mannerisms and now makes him work smarter, not harder when he is on-screen. In fact, there are faux-Hulot’s throughout the film, confusing both the spectator and various characters in the film itself.

This sort of refinement increases the enjoyability factor of the film, but it is hard to discover this fact until the very end.. There is quite a bit of slapstick involved, but it is so restrained as to be almost uncomfortable; the sound of hard shoes on a hard floor, the irrational modulations of ventilation systems, the unintelligible murmurs of smalltalk, all combines to make ambient sound its own character in the film. The whole environment of in modern city life creates unintentional hilarity after unintentional hilarity, and part of what strengthens this aspect is that none of the people in the film notice that something funny is happening; a facet that was not present in M. Hulot’s Holiday.

Every person in the film seems obsessed with being as modern [and to Tati, as ridiculous] as possible. There is an emphasis on protocol, following the directions of the modern manner and devices, when the old ways would be faster and less prone to confusion. At one point Hulot wanders into a trade show of new inventions and they are possibly the stupidest things ever invented. [e.g. a broom with headlights, a silent door [which sounds alright until you need to slam it for effect]]. The salespersons earnestly display their Ionic column trash cans and pantomime their use, and there are ubiquitous leather chairs that act like whoopee cushions whenever someone so much as touches them. But, all this is “modern” and so overlooked by people doing their best to appear modern themselves.

This is infuriating, and it all comes to a head in an interminable sequence at a night club that has opened even though construction on it hasn’t finished. In their haste to be modern they’ve neglected common sense on every level. The chairs ruin people’s clothing, they only had enough food for 27 people, the kitchen is completely unfinished, and the neon sign directs the bounced right back inside. Thankfully everyone thinks this is just part of the restaurant’s modern ambience and play along until the band gets frustrated and leaves. After this climax the people start acting like real people for a change and the atmosphere of the film ceases to be as bland in color [reminiscent of Le samouraï]and affect as it has for most of the film. It ends with a vibrant release of color, a roundabout becomes a carousel, and we get a feeling that there is something sublime about being so ridiculous.

Oh yeah, I almost forgot to mention the reference to Godard’s Breathless that takes place in the film. You couldn’t miss it if you tried.

• Criterion Essay by Jonathan Rosenbaum.

• Roger Ebert Review.

• Details on the reconstruction of the 70mm print.

• Senses of Cinema article on Tati.

• Cinematic Reflections article on the film.

• Five clips from the film on YouTube.